Last year Seattle’s North Central Little League canceled its baseball season, which was tragic for kids aged 7-13. More importantly, it was devasting for their hyper-competitive parents, whose entire existence is predicated on sacrificing their overall familial relationship for the sake of future stardom and financial gain. Or at least a scholarship.

And don’t forget those poor coaches with no one to yell at.

Okay, all coaches don’t yell, and admittedly it’s a tough business. Coaching kids’ sports takes quite a bit of patience, resilience, and a hole in your life you’re trying to fill by winning what amounts to a truly inconsequential game. I mean, it’s inconsequential statistics-wise – of course, the kids learn how to be part of a team, develop self-esteem, build resilience, etc., etc., if you think that’s important.

But, coaching takes an unbelievable amount of time when it comes to baseball. This is because a standard little league game/practice takes upwards of 14 hours, what with the walks and the beanballs and the nose-picking and the grass-examining and spontaneous outbreaks of wrestling. And that’s just the obvious stuff – don’t forget about stopping everything because the ball went into the street or onto the front lawn of that grumpy neighbor who’s completely flabbergasted by the fact that people are on his property despite living right next to a park.

Speaking of delays, there’s also that dreaded “I’m running late” text from a truant parent, so the coach has to sit with Billy-what’s-his-name on the bleachers for an extra 30 minutes after practice while all they really want to do is go home and drink a beer in the shower.

Or so I hear.

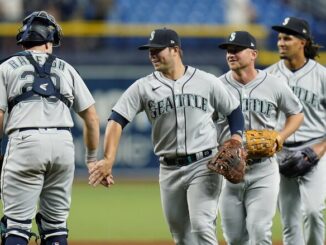

Actually, I know about all this. In 2019 my friend Josh asked me to be an assistant little league coach for the third year in a row. I reminded him that I (a.) don’t like baseball other than attending three Mariners games per year, preferably on sunny days, preferably with beer, hot dogs, and nachos, (b.) was a terrible baseball player as a child, and (c.) had no particular, specific skill to impart other than teaching the underperforming batters to call lots of time-outs at the plate in hopes of getting the pitcher off track (plus it’s fun to knock the infield dirt off your cleats as the major leaguers do).

It didn’t matter. Once again, Josh needed a living body, and I qualified.

The 2019 season was our first foray into real little league baseball as the kids were old enough to be in the “Majors” division and thus faced serious physical injury. I’d previously helped with tee-ball (talk about a snooze fest, but at least it required minimal effort), and what to me is the perfect division, the “Minors.”

The Minors was great fun – the kids showed a modicum of respect for authority while still being too small to generate much velocity when pitching/throwing/hitting, so you didn’t have to pay too much attention. Plus, to keep the game moving, the coaches took over pitching after ball four (I think), which gave the kids an actual opportunity to hit said ball. Also, the parents were only on the verge of psychotic behavior – you could see them just barely restraining themselves from screaming about how to coach, how to ump, or if you’re the child, how to get an NCAA Division One baseball scholarship.

Minors’ practices were the absolute best and involved hitting lots of pop flies to the kids, who comically scrambled and tripped and bumped into each other as they tried to catch/run from the ball. I think this was also the last division that could be co-ed, which is a shame because it’s always fun to watch preternaturally talented girl athletes absolutely smoke the boys – which hopefully taught those dirty chocolate and booger-covered mongrels a thing about diversity and inclusion.

There was a storm on the horizon, however. At the end of our Minors season, I remember casually walking up to an ump I’d never met at a field we’d never played on and asking him if I could stand in the back of the outfield to help coach my kids like I’d done all season. His response was to literally size me up, stretch to his full 6’4” height with all his battle robot umpire gear jangling, and state, “Not in my ballpark” with his hands on his hips all squared-off like he wanted a fistfight or to mount me. I’m not sure which. I responded, “Thank you, you’ve been very helpful,” and walked away, realizing the kids had grown big enough to enter a new era, and I wasn’t going to like it.

Indeed, the storm we faced the following season was the Majors division, and it was no joke. At our first practice, these kids who looked like they should be shaving showed up and threw the ball so hard I thought my hand was going to explode. And their batting stances indicated that yes, indeed, their fathers were former serious players, one of whom had another son actually playing NCAA Division One baseball, and Josh and I were screwed as our whole coaching philosophy focused on learning and having fun, which suddenly had no place here.

It didn’t take long to realize the extent of our doomed-ness. Our team, which the kids named “The Fighting Chinchillas” the previous year, now went by the unfortunate moniker of “Cube Smart,” thanks to that classic part of neighborhood Americana where local businesses show their community support and increase brand awareness at a relatively cheap rate by sponsoring youth sports teams. Cube Smart builds brand new buildings that at first look like nice condominiums. Still, it turns out they’re just nice apartments for the stuff that won’t fit in your house (or micro-condo, or rental), which seems to be the polar opposite of sustainability when you think about it.

Then, of course, the hierarchy of actual baseball skills became readily apparent to everyone involved. There were five really talented kids on the team, five decent athletes who could sort of keep up, and five terrible players. You could tell the terrible players because, at the end of practice or a game, they were the ones with blood on their faces, bruised arms, and instant chemical ice packs all over their bodies thanks to that hardball repeatedly smacking them as they batted/played catch/fielded/walked back to the dugout.

The attrition rate for terrible players the previous year was 0%. This year it was 75%.

The next sign of the apocalypse came when one dad insisted on calling me “coach,” like all the time, despite my protests, to the point I offered him the gig as it really seemed like he wanted the job or to be at least called “coach” himself. Then this other dad volunteered to help as our second assistant coach, but he was gone for the first three games, and when he showed up in the middle of game four, he totally lost it when he realized Cube Smart had amassed an 0-3 record in his absence. His mood did not improve when he realized I had benched his (all-star) son in the middle of this game so another kid could get some playing time.

And I mean, he really freaked out. I thought his head was going to explode when he saw the philosophy behind my batting order as well. (Secretly, I had no philosophy.)

We bumbled through the rest of the season. This dad became the de facto head coach, which was actually great for a while. He really knew his stuff and made a great effort to impart actual skill-developing drills into our practices, which the kids definitely benefitted from. However, The End arrived with three games left in the season, as we came to terms with our 3-7 record, and tensions ran high. During practice, this same gentleman got into a shouting match with one of our parents about why her kid wasn’t playing any position aside from right field, which is the graveyard position you stick horrible players (I should know, I spent five seasons in right field).

I wasn’t there for the argument, but I heard about it. When I saw her the next practice, I explained the dude “is a hard charger but means well,” to which this very Philadelphian woman responded with a series of very vocal criticisms mixed with the occasional profanity the coach’s wife and parents (who were apparently visiting) overheard.

Ugh.

I didn’t think much of it, there were only two weeks of practices and games left, but this gentleman must have been informed there was a conspiracy against him as he absolutely stopped talking to me and actually wouldn’t even stand near me, which I’m used to from my social life but was surprised to experience in the context of kids’ sports.

And the “hey coach” guy stopped saying “hey coach” all the time as well, which was somewhat of a relief actually.

To make matters worse, we accidentally won our second-to-last game when these guys were gone, and Josh and I put our crappier players in key defensive positions like shortstop. I think the “I’m not talking to you” coach took it personally, but really, like my batting order, it was based on absolutely nothing.

Our 2019 Majors season ended, which was the last time I’d coached baseball. Usually, I’m willing to try things again, but it hasn’t come up, and if asked, I’d definitely decline. Everything has a time and place, and as time passes, sometimes we get evolved out of a situation. And that’s not a bad thing.

But I did enjoy watching the kids play. Baseball is a great sport for just hanging out, and after being in my house all winter, the prospect of sitting in the sun and watching the Mariners is extra appealing – I’m glad today is opening day.