As the NBA plows forward into its ill-conceived All-Star weekend in the midst of an ongoing pandemic, I needed to remind myself why I spend time glued to the screen, fixated on super-human athletes who have an uncanny ability to throw a ball through a hoop.

The NBA has been a breath of fresh air during the pandemic, throughout the bubble and into this season, not only for its escapism (something we all continue to need) and wonderful entertainment value (if you happen to be a sports fan), but for its modeling of how to bring back sports successfully, even without fans in attendance.

Yet when I heard an All-Star game was in the works, despite a promise to the players before the season began that there wouldn’t be one, I was dismayed. The social conscience that the league embraced and embodied in the bubble to wrap up the 2020 season seems to have been forgotten.

As a fan, of course, the All-Star game provides not only an entertaining weekend, but a requisite break from the demands of following your team over the course of a six-month, 82 game schedule. With this season shortened to 72 games, and the pandemic still raging across the U.S., it seemed natural to forgo this year’s mid-season weekend exhibition. But this won’t be the case

I appreciated LeBron and Giannis speaking out against the All-Star game, but of course, they are going, along with all the other stars who aren’t injured. Fame walks, it seems, even in the land of gazillionaires.

While stricter travel and leisure protocols will be in place for the festivities in Atlanta, it still seems like a totally unnecessary and insensitive, even hypocritical endeavor for the league to hold. Especially in light of the recent Coronavirus variants entering the U.S., and the league’s steadfast support of the players’ actions this past year regarding racial and social justice issues (ending the pandemic is a social justice issue at this point, NBA!)

Nevertheless, the show will go on, the upper echelon will enjoy commiserating, and millions of people with nothing to do, still, will tune in. Bummer.

So I needed a pick me up; something to remind me how wonderful basketball is, be it on the blacktop or in the NBA, be it for bragging rights or for millions.

Ross Gay’s Be Holding seemed like the perfect antidote!

Gay won the National Book Award in poetry (among other prizes) in 2015 for his poetry book Catalog of Unabashed Gratitude and he recently returned to the limelight with his well-regarded book of essays, The Book of Delights (2019).

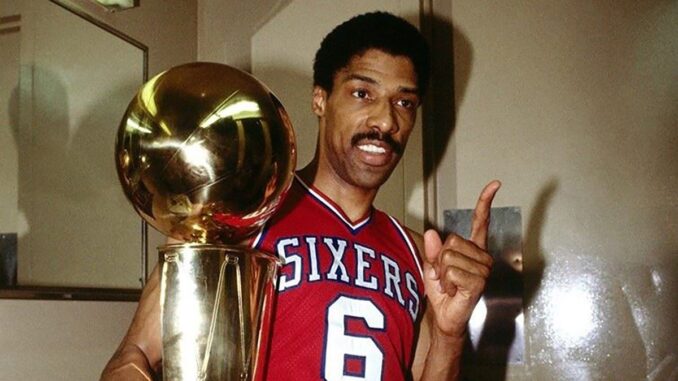

With 2020’s Be Holding, however, Gay bends the book-length poem genre by focusing his gaze on sport. Moreover, the genre-bending deepens when one realizes, fairly early on in Gay’s book, that the breadth of this poem is one basketball play: Dr. J’s famous up-and-under the backboard, one-hand palming, reverse lay-up against the Lakers in the 1980 Finals.

It is one of the most iconic shots in NBA history. Reverse Lay-up, Baseline Scoop. Whatever you call it, over forty years later, it is still unbelievable to watch. Watch it here if you have never seen it. Watch it again if you have.

Not only is it unusual to find poems devoted to sport (believe me, you have to look hard to find good ones), it is basically unheard of to find an entire book length sports poem. The fact that Gay devotes half of his 100 pages to one play is even more remarkable.

The poem is full of subtle twists and turns. Structurally, Gay has us imagine we are up all night with him (he keeps stating the time), creeping forward second by second examining the YouTube clip of Dr. J’s shot; Gay’s razor focus describing every angle; Gay’s imagination guessing at what Kareem and Mark Landsberger (who were under the basket), along with everyone else in the Spectrum, were thinking.

While the feat itself of carrying a three-second basketball play over the course of fifty pages of couplets (two lines of poetry put together) is noteworthy, what is even more refreshing is how seamlessly Gay slides in and out of Dr. J’s layup to other concerns or aspects of Gay’s life, some basketball-related, some not.

Gay discusses his own forays into pick-up ball. He takes up historically resonant photos, and conversation around being black in America. There are unflinching moments, to be sure.

Nevertheless, the photos are well-timed to break up the long text, and the main idea of Be Holding shines through by the poem’s close: the thought that we need to be holding each other up, literally, in gratitude, to get through this time; that we should be beholden to one another.

And it’s not just Dr. J that holds court in Be Holding. Other figures appear. Gay calls on Iverson’s famous speech near the close of the book, for instance, to hammer his points home:

we in here

talking about

the practice

of the beholden,

a practice

of being beholden,

talking about

how might I hold

my beholden out to you

and you hold yours out to me,

how do we be holding each other,

how do we be

beholden to each other

(91)

While a reader’s attention inevitably wanes over the course of an 100 page poem with no breaks (other than the photos), Gay does a remarkable job of keeping things both light and heavy, both entertaining and thoughtful, both humorous and meaningful. The poem ends, essentially, with Dr. J’s shot falling through the net.

In the end, perhaps the most revelatory aspect of Be Holding is that Gay defies the general trend of a book of sports literature to make its case for one or the other: the sports fan or the critic. Gay has crafted a marvel for both; an inspiring and innovative homage to the beauty of seeing a ball go through a hoop.