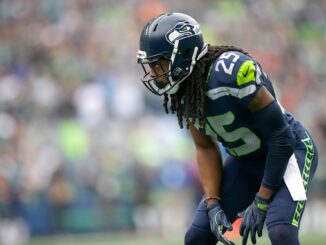

Richard Sherman is one of the most fascinating figures in the NFL. This is especially so for those of us from the Northwest (or California) who have, shall we say, history with Sherman.

And I don’t mean fascinating in any sort of hagiographic sense. I mean so in the kind of complicated, almost literary-like figure. He’s what some might call a well-rounded character—as opposed to a flat one.

Sherman is all too human. He’s full of flaws like hubris and braggadocio. He’s the type of player that I’m sure more than a few fans would like to just shut up, or go away.

I find him compelling because he challenges all manner of stereotypes. Some of it is perhaps unintentional; much of it, however, is by all too clever design.

Sherman has been labeled everything from a menace to a so-called “thug”. Perhaps because of some of his behavior. More insidiously, because he came from Compton, an area of Los Angeles known to some for its prevalence of gangs, violence, and criminal activity. But Sherman was very successful academically, both in high school and then in college, at Stanford. His academic credentials, in spite of his detractors’ criticisms, are impeccable.

He also might have taken a business course or two along the way. Or maybe not. At any rate, when the Seattle Seahawks cut him in the spring of 2018, he opted to represent himself in negotiations, rather than go the more traditional route of hiring an agent. Many wanted to say that his decision was as foolish as representing himself in court. But the outcome—a three year, 39-million-dollar deal with San Francisco—looks now like he was a pretty good negotiator.

On the football field, he has continued to excel long past what might be called his “prime”. Notwithstanding his poor performance in the Super Bowl this year with San Francisco, which must have been a deeply humbling experience for him, he should still be viewed as one of the best players at his position in the entire league.

It’s where we look at the specifics of his professional career where things get interesting. Drafted in the fifth round of the 2011 draft, the 25th cornerback taken (!), no one was expecting him to be so special. We know that he came to Seattle at the right time. Just as Russell Wilson and others were arriving. As then-new coach Pete Carroll was building the juggernaut that the Seahawks would become in ensuing years. That said, he had to fight his way up the depth chart before he became the player we know him to be today.

Sherman was brash, on and off the field. He wasn’t afraid to speak his mind in front of a microphone or a camera. There were more than a few feathers ruffled along the way. Some thought his sideline conversation with Erin Andrews in 2013 was way over the line. Hence some using the term ‘thug’ to describe him. But Sherman shot back, correctly pointing out the outdatedness of that loaded term, hopefully helping to change the way we think and talk about football players and professional athletes in general, especially African-American ones.

He was seen as a leader of the Seattle Seahawks when they won their first Super Bowl following the 2013 season. Likewise for the Super Bowl team the following season. But it was the way that game ended that led to a shift in Sherman’s feelings about his team. He supposedly was not happy with Pete Carroll for the infamous play call that ended that game against the Patriots; he didn’t seem to have any love lost for quarterback Russell Wilson either, according to reports from the time.

But as he has done time and time again, Sherman remade himself as a 49er and found himself playing in his third Super Bowl. Add in five years as an All-Pro, and he will likely end up in the Hall of Fame.

The funny thing is that he could continue to play longer and accrue more accolades. It would be ironic, though unlikely, if we came to think of him more as a 49er than as a member of Seattle’s Legion of Boom secondary.

Perhaps the only constant will be Sherman’s outspokenness. His belief in himself and his abilities, in spite of what his haters might say.