On occasion, Oregon Sports News will highlight a significant figure in Portland Trail Blazers history. After 50 years, plenty of triumphs, and many tragic blunders, the Blazers’ past is a rich gold mine that isn’t tapped into nearly enough. We’re going to change that. Welcome to the Trail Blazer History Highlight.

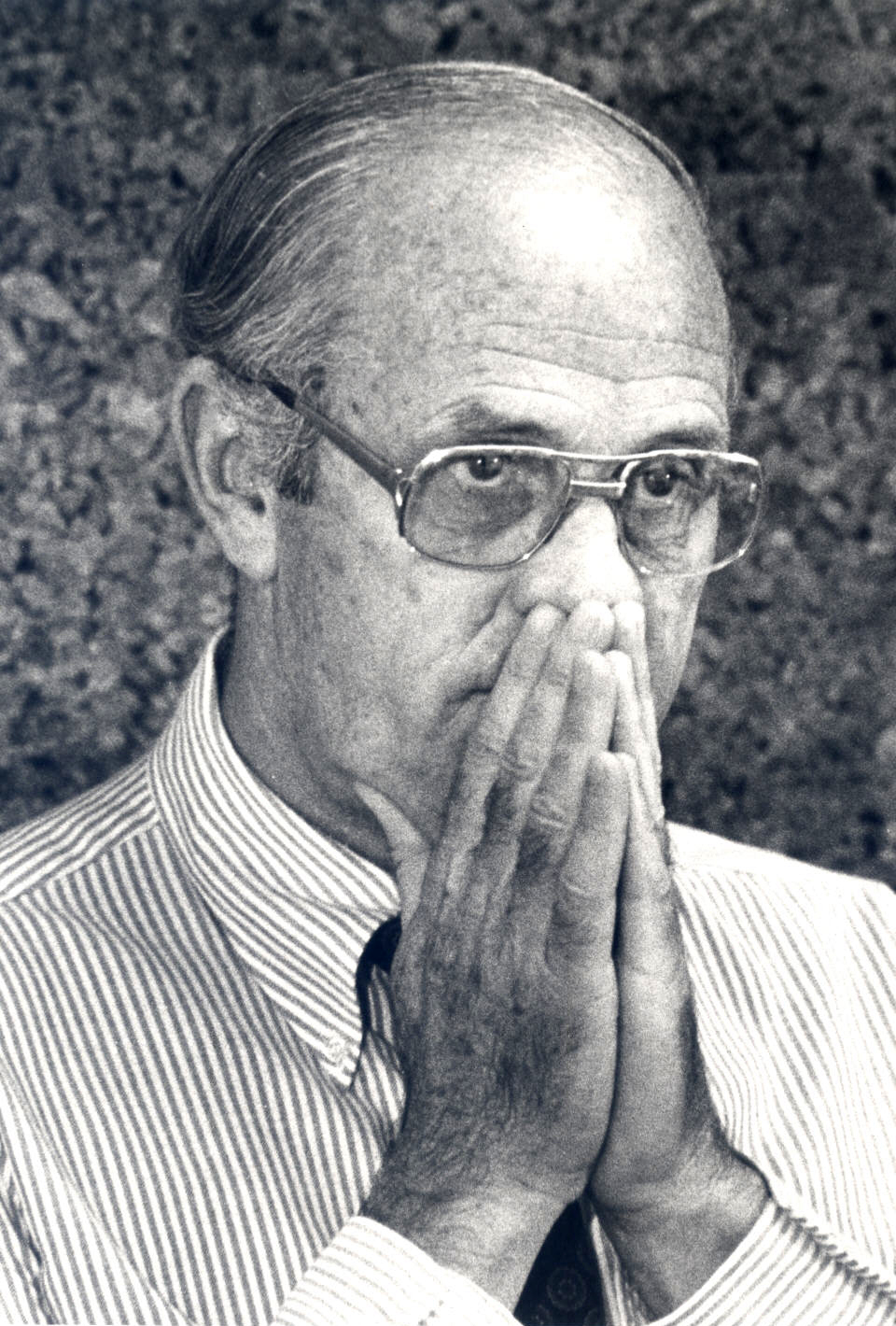

Today, we take a look at the scout and front office executive that shaped the first 16 years of Blazers history, Stuart Inman.

How He Got Here

Inman was a California kid, born in Alameda in 1926. He went to San Jose State, playing for four years in their basketball program. His bio listed him as a guard/forward/center, a polite way of saying he was either a bulky enough 6’4” to play center, or too slight at 6’4” to play anything but the point, depending on the competition.

Ever seen the Game of Zones series on Bleacher Report’s YouTube channel? I’ve been a huge fan of that series, and not just because I’m enough of a basketball nerd to get all the references. A couple years ago, during an extended bit about Thon Maker’s misreported age, Giannis Antetokounmpo and friends discovered a mural featuring a bunch of smallish white figures frolicking around tall, dark fir trees. Giannis says, “Oh, those are the White Dwarves, mythical creatures from the beginning of time!”

Well, Inman was one of those White Dwarves—or would have been, more precisely. He was drafted to play in the fledgling NBA in 1950, but chose to coach high school ball in California instead.

The reason why Inman gave up the chance to be a pioneer (the NBA had just merged with a couple other leagues in 1950) was simple, understandable, and always on the minds of people not lucky enough to be a part of the Lucky Sperm Club: money. Moving across a continent—no small feat in 1950—for the chance to make maybe $4,000 a year playing for a team that might fold and will miss a check or two wasn’t as attractive as coaching and teaching in Northern California to Inman.

Even in that environment, Inman had a very keen eye for talent. As he rose from coaching in high school in the fifties to coaching junior college ball in the sixties, he became a source for those big-time colleges and NBA teams looking for diamonds in the rough; this will be relevant later, not only because it led to Inman getting his big break, but because he was THE diamond in the rough finder in the 1970s.

How did Inman get the job? According to Wayne Thompson in Blazermania: This Is Our Story, Harry Glickman, the team’s founder and first general manager, was going to act on a tip from his counterpart in Seattle, Bob Houbregs. Glickman was going to hire Donnis Butcher, a former player and coach for the Detroit Pistons, until he got a phone call from Art Johnson, a promoter from San Francisco. Johnson told Glickman that this forty-something college coach named Stu Inman had perhaps the brightest basketball mind in the planet—a statement seconded by none other than Bobby Knight himself.

Swayed by the recommendations, Glickman hired Inman to run the personnel department, and would go on to call the Inman hire “the best decision I ever made.” But how well did Inman do the job?

His Time in Portland

Nowadays, there are many duties an NBA general manager must perform, but he also has a huge staff assisting him—especially with scouting. The buck stops with him, but others always get the ball rolling, whether it be those above him pressuring him to trade for Player X or deal away Superstar Y, demands from Disgruntled Player Z to leave town via trade, or members of his staff telling him that Awesome Prospect A is more awesome than Incredible Prospect B is incredible, or vice versa.

In Inman’s day, he had to deal with maybe 90% of the workload, with less than 10% of the staff. In the earliest days, he was basically a staff of one; the coaches might give input, and Glickman sometimes offered a stray thought, but Inman trusted few people and made decisions basically on his own, typically after spending weeks and months on the road scouting. The results, over a 16-year career that was full of acrimony with agents, struggling against a tough and cheap ownership, and a certain cynicism as the malaise of the post-title Blazers bled into the first round-and-out 1980s, were full of highs and lows.

The kind of player Inman loved most, to provide some context, was the undervalued, small-school kid without much hype behind him. So it’s not a surprise that some of his favorite—and best—draft picks were guys like Larry Steele (1971), Dave Twardzik and Lloyd Neal (1972), and Bobby Gross (1975), members of the 1977 championship team, whose jerseys have all been retired by the Blazers. Other than the number 1 (retired to honor principal owner Larry Weinberg) and 77 (honoring Dr. Jack Ramsay), every retired number belongs to a player drafted by Stu Inman. (At least, until certain men that wear/wore 3, 7, 12, and the Letter O join them.)

As for his first-round picks, Inman was hit-or-miss. It was pretty easy to select Bill Walton first overall in 1974, and Lionel Hollins was another great one, but he also had some serious whiffs and missteps. It isn’t a stretch to say Inman’s draft day adventures altered the history of the NBA.

I’ll go over the Blazers’ draft history during draft season (it’ll be some painful research; hell, it has been already, and I haven’t even dived that deep), but here’s a short bullet list just of Inman’s mistakes:

- In 1973, Inman took LaRue Martin over Bob McAdoo. Stu gets a pass here, since Herman Sarkowsky, the leader of the Jewish triumvirate that owned the Blazers before Weinberg gained sole control, was insulted enough by Mac’s agent jacking up his contract price that he overruled Inman and told the agent to go to hell. Martin washed out of the NBA within four seasons. McAdoo led the NBA in scoring three times, was a five-time All-Star, won two NBA championships, was the 1975 MVP, and is one of the 60 best players of all time.

- In 1976, Inman took Wally Walker over Adrian Dantley. Walker was a handsome white forward that loafed his way out of Portland after just two seasons, being traded to the Sonics; Dantley was a black forward who went on to have a 15-year career, racking up over 23,000 points. He’s one of the 80 best players of all time.

- In 1978, Inman decided to draft Mychal Thompson instead of acquiring the draft rights of a college junior-eligible named Larry Bird. Bird wasn’t willing to leave college right away, so Inman (or maybe Weinberg) pulled the trigger on Father of Klay. Thompson couldn’t live up to the hype of being No. 1 overall (a trend for Blazer bigs taken highly), while Bird … look, if I have to explain why missing out on Larry Bird is a bad thing, what are you doing here?

- In 1984, Inman infamously took Sam Bowie instead of Michael Jordan. Wayne Thompson in Blazermaniatried to defend Inman’s decision in a two-page essay, but it was honestly less of an argument and more about Wayne trying to cover for his friend. Wayne failed to point out two crucial things: Drexler played small forward in college, so it was not out of the realm of possibility to play both Drexler and Jordan together, and that Jordan was even then a budding superstar who was a no-brainer to pick, even on a team with 15 guards. Push comes to shove, you ditch Drexler for Jordan.

- This isn’t related to the draft, but Portland had a young man come into camp from the ABA one summer. His name was Moses Malone. His contract was very expensive, but he played well with Bill Walton and Maurice Lucas, and had the potential to be great. Weinberg told Inman and Ramsay to cut him because of that contract. Moses is one of the 20 best players of all time—top 15 depending on how you feel about Julius Erving, Bob Pettit, and Dirk Nowitzki.

To be clear: I’m not trying to crap all over Stu Inman. He was a brilliant executive that found talent in the unlikeliest of places (remember Billy Ray Bates?), made savvy trades like the one that brought Lucas to Rip City as Walton’s enforcer, and was regarded by his peers as perhaps the best basketball mind in his day. He absolutely deserves to be in the Hall of Fame as the architect of perhaps the most aesthetically pleasing championship team in history, igniting a fandom phenomenon that has impacted this city forevermore.

He did lay the groundwork for the early 1990s Blazers teams as well, drafting Drexler, Terry Porter and Jerome Kersey. His tutelage of Morris “Bucky” Buckwalter, who was an assistant coach to Ramsay in addition to being a scout, ensured Portland was in good hands after he left in 1986. Buckwalter left his own mark by drafting Arvydas Sabonis and Drazen Petrovic, and trading for Kevin Duckworth.

Unfortunately, Stu Inman is remembered more for his failures than his successes, even though most of the former likely weren’t his complete fault. No matter how great he was at judging talent, no matter how steadfastly he persevered through ownership being tough, players being mercurial and moody, or how deftly he kept up with the changes of the league, he’ll always be remembered for choosing Walker, LaRue, and Bowie over Dantley, McAdoo and Jordan.

Post-Blazers

Inman worked in the front offices of the Milwaukee Bucks and Miami Heat before retiring to Portland. He died on January 30, 2007 at age 80.

Part of me feels sorry that Inman—whose high importance on drafting for character and talent in that order is a trait that the Trail Blazers organization was famous for until Bob Whitsitt arrived—never got to see the post-Jail Blazers’ resurrection be completed before his heart attack. He would have loved Brandon Roy and Damian Lillard.

Random Nugget O’ The Day

There are several Inman anecdotes in The Breaks of the Game, David Halberstam’s magnum opus about the post-Walton Blazers (the 1980 Blazers, to be exact). Although the contract troubles with Lucas and Hollins weighed very heavily upon Inman in the book, he was said to have an affable manner about him; Halberstam compared him to a slick used-car salesman. He also was a notorious chain-smoker.

(Working out and staying fit are all well and good, but human life in the end is quite random. I’ve heard of super-fit people dying of random causes after barely reaching 60, and people like Inman and my grandmother surviving into their 80s after a life of chain smoking, booze guzzling, and coffee inhaling. Makes me feel a little better about not going to the gym, I’ll say that much.)

Inman also had a fascination with college fight songs and weird team names. For example, Jack Ramsay, his coach for 10 years, used to play on a semi-pro team called the Sunbury Mercuries. Whenever they would argue about a procedure, or if Ramsay would complain about a player not doing his job, Inman would needle him by saying “Is that how they used to do it on the Sunbury Mercuries, Jack?” His idea of an icebreaker was guessing a person’s college fight song, and humming it.

(I’d say that was weird, but I’m paired with a woman that puts salt in her coffee, so….)

Lastly, Inman was not at games very often during his time running the team. He was on the road scouting most of the time; that lure of finding the gem in the sand never left him while he was working in the NBA. When he did attend practices, the players were extremely apprehensive around him. Not that he was a bad guy or a jerk to them; indeed, his affable nature extended to the players he felt comfortable around. When he did attend practice, and put his arm around a player while talking to him about this and that, the players said that was a sign that you were about to be traded or cut, and they used to move to the other side of the gym whenever they saw the Shadow (their nickname for Inman) apparate into the area.